State-Wide Resources

and

The Land Acquisition Process of

the Colony and State of Pennsylvania,

1682-today

Land Transferred from Colonial or State Government to Private Individuals:

The normal process for obtaining land in Pennsylvania involved a 5-part process set up under the Crown of England: (1) the applicant submitted an application for a land tract; (2) the Pennsylvania Land Office issued a warrant, or order, for a survey; (3) a survey was conducted; (4) the loose survey was returned to the Land Office for issuing the final title or “patent”; (5) the patent was issued and a name given to the tract by the patentee (see the overview at the Pennsylvania State Archives). It is estimated that approximately 70% of land within Pennsylvania was transferred from the colonial or state government to private owners using this process. Expand each of the four items below for more information on this process. Download a printable handout of this process here.

We have just published the 2nd edition (2024) of The Keystone: Essential Guide to Pennsylvania Historical County Records that brings online resources for all of the following topics together for each of the 67 counties into one 548-page book. Included are links to each county’s online Deed Books and indexes, online county history books, online 19th-century maps showing landowners, online registers (ledgers) for warrants & patents, online registers for military land grants, evolution of the counties and townships, etc.

However, in perhaps 30% of land transfers, different processes were used:

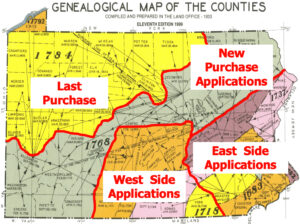

- Many early settlers settled on vacant land before paying for and receiving government authorization (a warrant), often because they were beyond government offices or because Pennsylvania had not acquired the territory yet through treaties with Indians. Rather than receiving a “warrant to survey” ordering a surveyor to come and survey the land as in the normal process, they received an “order to accept” a survey conducted after their settlement. In this case, the survey states it was conducted on a “on a warrant to accept” and the word “accept” is noted in the relevant Warrant Register. For more information on land obtained through treaties and the different Warrant Registers opened for each (East Side Application Register, West Side Application Register, New Purchase Register, and Last Purchase Register), expand the “Indian Treaties” section below.

- Land was given to Revolutionary War soldiers either to compensate them for their depreciated pay (“Depreciation Land”) or to entice them to stay in the Continental Line to the end of the war by the promise of free land (“Donation Land). For more information on these lands and the ledgers opened for these people, expand the “Depreciation and Donation Land” section below.

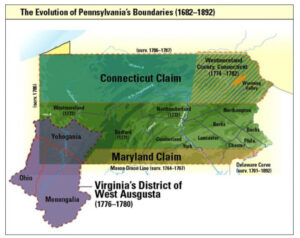

- The boundary dispute between Pennsylvania and Virginia was eventually settled in 1780 when Pennsylvania agreed to accept claims made by settlers who purchased from Virginia. Expand the “Boundary Dispute: Virginia vs. Pennsylvania” section for more information. Two other boundary disputes, one between Connecticut and Pennsylvania and the other one between Maryland and Pennsylvania, are also explained in this section.

We offer 4 major resources for locating the earliest private purchasers of land across Pennsylvania for sale: (1) a set of Warrant Registers for the entire state ($35; 70 pdf downloads in the set); (2) a set of Patent Register Indexes ($35; 10 pdf downloads in the 1683-1995 set including Patent Register Indexes A-AA, P1-P65, H1-H80) for the entire state, (3) a set of Tract Name Indexes from 1682-1959+ ($25); and (4) the New Purchase Applications Register ($15). We also offer a comprehensive set of Warrant, Patent, and Tract Name Indexes (pdf downloads, $80). See information about each of these registers in the information below. Remember that all of these registers, or ledgers, predate the deed books at the county courthouses. They are official Pennsylvania documents that record the transactions of the very first individual landowners of the colony and the colony or state of Pennsylvania, those who received their land from the colony or state.

Person-to-Person Sales:

Once a piece of land was transferred from Pennsylvania’s government to a private individual, all future sales were recorded as deeds in the county that included the land at the time of the transaction. Not all land passed through deeds–many times tracts were transferred through wills and private sales and these transactions that may be found in county repositories. See the section on deeds below for more information on county boundary changes and for searching online in Deed Books.

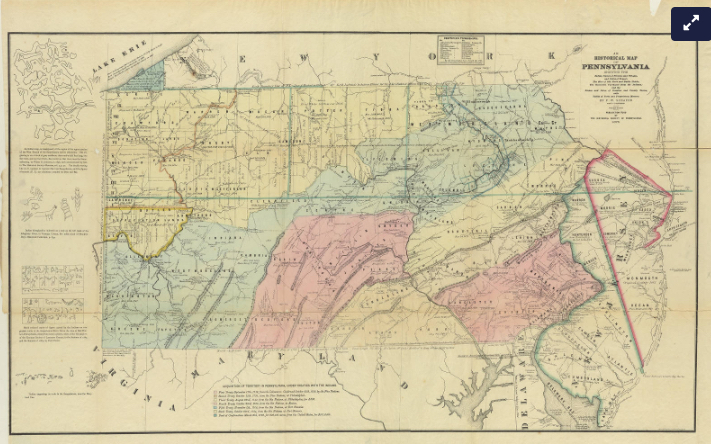

For an amazing map showing Indian purchases (shown in different colors), Indian names of rivers, historical events, Donation and Depreciation Lands, Susquehanna Company claims, Connecticut claims, old forts, etc., see “An Historical Map of Pennsylvania” by P.W. Sheafer (Philadelphia: Historical Society of Pennsylvania, 1875). Click on the image which will take you to the PennState University Libraries site, then expand it and zoom in.

Click on the + for each heading below to read expanded information about topics and see examples for some of them. Click on the – to close a topic and then + to open the next one.

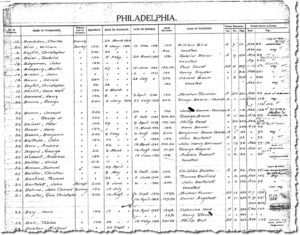

Philadelphia Warrant Register, Boone Entries

Philadelphia Warrant Register, Boone Entries

- The prospective landowners filed their applications for land in fairly general terms, often referencing a stream or a neighbor.

- When the Land Office received the application and fee, they issued a warrant, or an order, to have a Deputy Surveyor travel to the desired tract and physically survey it. The applicant had to pay a fee for this warrant and became known as the warrantee. The warrantee had the right to settle on the land, “improve it” by erecting dwellings and raising crops, and even transfer it to another person by will or sale. However, the warrant did not bestow final title on the warrantee. The settler had to pay another fee for the surveyor to come and therefore often waited many years before exercising the warrant and paying for a survey. Many of these loose warrants are on Ancestry.

- The loose warrant was summarized into a county ledger called a Warrant Register.

- The Warrant Registers are organized by county (at the time the warrant was issued), then by the first letter of the surname, then chronologically as warrantees received their warrant.

- The Warrant Registers contain a column showing whether a “Warrant to Survey” or a “Warrant to Accept” was issued. Pennsylvania’s process specified that settlers were to obtain a Warrant to Survey before moving onto a tract. However, many people moved west into vacant territory before receiving a warrant and simply “squatted” or “preempted” the process and became known as preemptioners. As more settlers filled in, the original settlers received unofficial rights to the land as the first claimant, but they had to pay for a “Warrant to Accept” the survey to be conducted and could not dispute it.

- The Warrant Registers are official documents of Pennsylvania. As the description of Warrant Registers published by the Pennsylvania State Archives states, “This is the primary finding aid for locating patents and surveys [in the Archives] when the name of the warrantee is known. Information given is warrant number, name of warrantee, type of warrant, acreage warranted, date of warrant, date of return, acreage returned, name of patentee, the patent volume, book, and page number and the survey book and page number. The names of the warrantees and warrant dates extracted from some of these registers were published in Pennsylvania Archives (series 3) volumes 24-26, but the published version omits the warrant numbers, return of survey information, and patent information.”

- The Warrant Registers document the first owners of land for approximately 70% of Pennsylvania and cover each county. For information about the remaining 30%, expand the “Indian Treaties” and “Revolutionary War and Donation and Depreciation Land” topics below.

- The Warrant Registers show both the warrantee and patentee, dates of the transactions, and the Patent Book and Survey Book for each tract. We looked up thousands of warrantees in the relevant Warrant Registers to find Survey Book and page number references for our atlases.

- All of the county Warrant Registers are posted for free on the Pennsylvania State Archives website where each page of each county’s ledger is a separate pdf file.

- Through a unique partnership with the Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission, we purchased all of the Warrant Registers from them and received permission to publish them. If you are conducting research on more than one ancestor in Pennsylvania, we suggest you download and save our set of 70 pdf files on your computer so that you “page through” the files and always have access to them, even when there is no internet connection: Warrant Registers of the Colony and State of Pennsylvania, 1682-ca 1940 ($35; contains the set of scanned images of 70 files: 3 pre-1733 “Original” and “Old Rights” ledgers, plus 1 Warrant Register for each of the 67 counties).

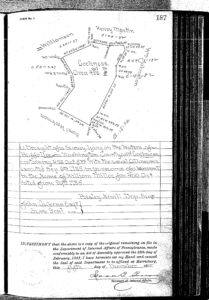

Survey Book C132, pg. 483: James Chesnut in right of his grandfather Daniel McFarlin, Lancaster Co., 1746

- The next step was to pay a fee for the survey and wait until a deputy surveyor could be assigned to do the work. The results of the survey were returned to the Land Office with a precise description and map of the tract, nearly always including the names of the neighbors who owned the adjacent tracts at that time.

- These loose surveys are on file at the Pennsylvania Archives in Harrisburg and have been copied into Survey Books that are now digitized and online.

- Be sure to examine both the front and reverse side of surveys. Take note of the neighbors–they may be relatives, witnesses for wills, godparents or sponsors for births, and fellow soldiers. Neighbors’ names may not be shown but often another Survey Book and page number will be noted on the survey and you can look up who owned the tract to see if there is a relationship.

- We made diligent efforts to supply the Survey Book and page number in our atlases when the Land Office draftsmen omitted them by consulting the relevant Warrant Register for the time of the sale. Many of the revised editions contain newly supplied survey references.

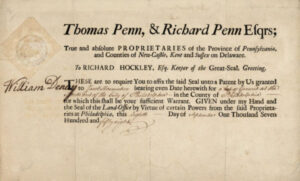

- The last step was to pay yet another fee to the colony or state and receive the final title which was called a patent. This is the official transfer of ownership from the colony or state to an individual. He or she now became the patentee.

- In our experience, perhaps 60-70% of the warrantees of a county were also the patentees. Often, however, the original warrantee died and the land passed to a relative or was bartered (sometimes for a gun or a coat) or sold to someone else; or he stayed on the land for a short while before moving on (usually west) and transferred the land to someone else who then patented it and became the patentee; or he was a speculator who never intended to settle on it and transferred ownership to someone else to then patented it.

- Patent Registers cover specific years. Names are entered into grouped alphabetically by the first letter of the patentee’s surname, then grouped by volume number of the Patent Book, and finally arranged more-or-less chronologically by date of patent.

- Patent Registers document the final title passed from PA’s government to private owners and thus precede the deed books located in each county.

- Sometimes many years and several owners passed between the issuance of the warrant, survey, and patent.

- The patentee gave a name to the tract in order to track future transactions, sometimes descriptive but sometimes indicating his European origin.

- Patents were copied into ledgers called Patent Registers and are grouped into series:

- Series A-AA (1683-1781): Volumes A1 – A20, Volumes AA1 – AA20, and Commission Books A-1 through A-4

- Series P (1781-1809): Volumes P1 – P65

- Series H (1809-1995): Volume H1 – H80

Through a unique partnership with the Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission, we purchased all of the Patent Register Indexes and received permission to publish them as Patent Register Indexes of the Colony and State of Pennsylvania, 1684-ca 1957 ($35). The set of 10 pdf indices can be downloaded and saved on your computer so that you always have access to them, even when there is no internet connection, are as follows:

- Index 1, Series A-AA & Commission Books 1683-1781

- Index 2, Series P, Vol. P1-P19, 1781-1794

- Index 3, Series P, Vol. P20-P35, 1792-1800

- Index 4, Series P, Vol. P36-P43, 1799-1809

- Index 5, Series P, Vol. P44-P65, 1800-1809

- Index 6, Series H, Vol. H1-H20, 1809-1823

- Index 7, Series H, Vol. H21-H40, 1823-1839

- Index 8, Series H, Vol. H41-H60, 1823-1839

- Index 9, Series H, Vol. H61-H76, 1864-1903

- Index 10, Series H, Vol. H76-H80, 1903-1995

- From 1733 until about 1810, tracts were given names to make it easier to track them when they changed ownership.

- If you only know the name of a tract, these registers will show you the name of the patentee, the date of the patent, the size of the tract, the name of the warrantee, the date of the warrant, the county where it was located at the time, and the volume, book, and page number where the patent is recorded. However, the relevant Warrant Register must be consulted to find the Survey Book and page number.

Through a unique partnership with the Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission, we purchased all of the Tract Name Indexes and received permission to publish them as Tract Name Indexes of Patented Land in the Pennsylvania State Archives, ca 1684-1811 ($25). The set of pdf images of the registers can be downloaded and saved on your computer so that you always have access to them, even when there is no internet connection.

The set of Tract Name Indexes include:

- Patent Books A-AA (1733-1781)

- Patent Books P1-20 (1781-1794)

- Patent Books P20-P35 (1792-1800)

- Patent Books P35-P43 (1799-1800)

- Patent Books P44-P65 (1800-1809).

After the Pennsylvania colonial or state government transferred title to an individual owner, all subsequent sales were recorded as deeds in the county courthouse–as the county existed at that time! There are three ways to access deeds for your ancestors:

- Go in person to the relevant county courthouse. This is by far the best technique because you can scrounge around for other documents (probate, court, tax, etc.) that will be stored there or nearby. Expand your search to nearby courthouses if possible, and look for churches your ancestors might have attended if you know their denomination.

- Of course, not everybody can get to courthouses, so the next best thing is to search Deed Books online. While some indexes are being created online for the entire run of each county’s Deed Books, you must usually search the Grantor Index and/or the Grantee Indexes (for the seller and buyer, respectively). This is tedius because so many Pennsylvania counties used the dreaded Russell Index (also called the L-M-N-R-T Index–watch the excellent 20-minute video by the Butler Area Public Library on how to use it. Most of the Deed Books for Pennsylvania counties are online and free at FamilySearch.org (but you need to sign up for a free account to search them). To find how each book is indexed, check the inside cover of each Deed Book. As time goes on, more and more Deed Books will be indexed online, but you will probably have to search in unindexed books for now. Here’s an article I wrote explaining how to search unindexed Deed Books that I hope will be helpful. UPDATE: FamilySearch.org has recently run all of its handwritten deeds through Artificial Intelligence (AI), making all names (including those not indexed such as witnesses and neighbors) discoverable. This AI capability is still in its beta stage (March 2025) but absolutely try its “Full-Text Search“ for names, locations, geographical features, etc.

- Last, hire someone to do on-site research for you. This can be expensive, but it will probably be less than the airfare, hotel, and car rental or other transportation you would have to pay for if you have to travel far.

Next, because county boundaries changed over time, starting with the three original counties of Philadelphia, Bucks, and Chester and ending with the 67 counties we have today, you must know when each was formed so that you can go to parent counties for more information if your ancestor settled in an area before the county was created. There are a few resources that will help you do that.

- Newberry Atlas of Historical Boundaries covers all counties in the United States, including time periods before statehood. Here’s an article I wrote about the atlas that you may find useful.

- For Pennsylvania counties, see the “Genealogical Map of the Counties” showing how each county evolved from parent counties. You can right-click on the image and save it to your computer as well.

To Pennsylvania’s credit, no land was sold under the colonial government until treaties were promulgated with resident Indians. Many people, however, settled as “squatters” or “preemptioners” on vacant land and built a cabin or planted crops. The Land Office promised to evict anyone who had not obtained a warrant but they didn’t follow through, and even more squatters settled on vacant land as immigration from Europe accelerated. Before the French and Indian War broke out, the British arranged five treaties that extended legal settlement to the Allegheny Mountains because settlers had already encroached on Indian land:

(1) 1732 opened land along the Schuylkill River waterways

(2) 1736 opened the Susquehanna River watershed

(3) 1737 annexed the infamous “Walking Purchase” triangle

(4) 1749 enlarged Bucks, Lancaster, and Philadelphia Counties

(5) 1754 set the western line for settlement at the Allegheny Mountains. Thousands of squatters settled on these lands. In 1765 a major shift was made by Pennsylvania authorities permitting squatters who were willing to accept a subsequent survey to apply for land and pay the original purchase price of the property with back interest dating to their settlement. They set up an application system with the following process: an application, usually on a strip of paper, was transcribed into a book known as the “East Side Applications Register” (containing 4,160 warrants) for the east side of the Susquehanna River, and another book known as the “West Side Applications Register” (containing 5,595 warrants). After a warrent was received, the claimant was expected to follow the same established process of paying for and having his land surveyed and then paying for the final title (patent). These East Side and West Side Application Registers give the date the warrant was issued, the number of the warrant, name of the warrantee, usually the name of the patentee, size of the tract and location, and Survey Book and page number (see column between the “Applicant” and “Description” columns.

New Purchase

At the end of the French and Indian War, a treaty was negotiated at Fort Stanwix in 1768. The area affected by the treaty was called the “New Purchase.” It opened up a vast swath of land cutting through Pennsylvania to legal settlement. On 23 Feb 1769, the Land Office advertised the sale of the newly purchased land, and applications began to pour in. In fact, by the designated date, 2,802 applications had reached the Land Office. Sometimes two or more applications were submitted for the same land. In order to make the process as fair as possible, a lottery system was devised. All of the applications received during the first 10 days of May 1785 were put into a lottery wheel and drawn out one at a time. Each New Purchase Application was numbered sequentially and the tracts requested were awarded on that basis. (When a tract of land was applied for by two or more parties, the earliest application was the one which received the tract.) Search by the warrantee’s name and number in the New Purchase Register online at the Pennsylvania State Archives site where each page is a separate file or use our downloadable New Purchase Register ($15)

Last Purchase or Purchase of 1784

As soon as the Revolutionary War was over, a new treaty at Fort Stanwix was negotiated between the United States and the Ioquois League which added a huge territory for legal settlement. The Six Nations surrendered their rights to all of the remaining land they claimed in Pennsylvania for $5,000. This treaty covered land now included in Butler, Clarion, Jefferson, Elk, Cameron, Potter, Warren, Forest, Venango, Crawford,Mercer, and Lawrence Counties. It also included parts of Beaver, Erie, Allegheny, Armstrong, Indiana, Clearfield, Clinton, Lycoming, Tioga, and Bradford Counties. The only area excluded was the triangle at the top of Erie County which was finally obtained in 1792.

Many families had settled illegally in these areas before 1784, but Pennsylvania gave them first rights to claim land if they could prove they had settled prior to 1780. The land transactions for these settlers are entered in the Northumberland County Warrant Register under the warrantee’s name; all of these warrants are dated between May and October 1785, just after the Land Office began to grant warrants in the area. Next, the state conducted the “Northumberland Lottery” whereby all applications for land in the Purchase of 1784 received from May 1-10 were placed in a lottery wheel and drawn. After each application was drawn and the purchase price paid, a warrant was issued that could be used for land anywhere east of the Allegheny River within the “Last Purchase.” These warrants are filed at the end of the Northumberland County Warrant Register and are available on the Pennsylvania State Archives “Northumberland Lottery Document Images” page. All are dated 17 May 1785.

The “Last Purchase” area was divided into two sections: (1) west of the Allegheny River and Conewango Creek was set aside for Depreciation and Donation land for Revolutionary War soldiers (see the “Revolutionary War and Donation and Depreciation Land” section below), while (2) the area east of the Allegheny River and Conewango Creek was set aside for normal purchase.

Speculators purchased thousands of acres on credit or depreciation certificates they acquired from soldiers with no intention of settling in this area. Quite a few speculators became obsessive about acquiring thousands of acres and were then bankrupted when they could not find buyers and land values fell. Squatters were given preference to encourage settlement, and therefore settling on the land before it was surveyed became the preferred method of acquiring land. A new law in 1792 required the warrantee to occupy, clear and cultivate 10 acres for every 400-acre tract within two years. These transactions are recorded in the “Last Purchase Warrant Register.”

The French and Indian War was fought over ownership of the Ohio Valley. It was inadvertently triggered in May 1754 when 22-year-old Lt. George Washington’s small expedition of Virginians and Indians, sent to “encourage” the French to withdraw from the Pennsylvania frontier, attacked a small French force warning the Americans to stay away from Pittsburgh. In July 1755 British Gen. Edward Braddock was sent from England with two regiments of British regulars to clear the French from the frontier, and Washington joined him with American troops. Benjamin Franklin gathered supplies, wagons, and drivers for the expedition in eastern Pennsylvania. Braddock was decisively defeated by the Indians and French, who then unleashed their fury against settlers west of the Blue Mountains. Most settlers east of the mountains fled to safety behind the Blue Mountains in Northampton, Berks, and Lancaster Counties. Numerous accounts of individuals who were killed, wounded or carried off have been printed. The war had three results: (1) the French lost their territory east of the Mississippi River while the British gained it; (2) the king announced the Proclamation of 1763 prohibiting white settlers beyond the Appalachian Mountains and establishing a buffer zone with the Indians, sparking American anger; and (3) Britain was nearly bankrupted, causing a new push for revenue through taxes.

State Records

Service Records:

During this war, most of the defense against Indians and their French allies was borne by the colonists who enlisted in local militias or formed ad hoc units. Since they were not part of the British Army, few records such as muster rolls exist. For transcriptions of the muster files that exist, see two sources:

- Pennsylvania Archives, Fifth Series, Vol. 1, “Officers and Soldiers in the Service of the Province of Pennsylvania 1744-1765,” pp. 1-368 (click on the “Browse” tab). The index is in the Sixth Series, Vol. XV (parts I and II). Company returns covering 1744-1765, most of which contain the soldier’s name and date of enlistment while some include enlistees’ name, age, where born, date of enlistment and occupation.

- Pennsylvania Archives, Series 2, Vol. II, also named “Officers and Soldiers in the Service of the Province of Pennsylvania 1744-1764,” 419-528.

- Entries in the Pennsylvania Archives whose titles are followed by an “a” were transcribed from documents in PHMC and the originals are there. If a “c” follows the item, the original is probably in the Pennsylvania State Archives but could alternately be in the Historical Society of Pennsylvania or even perhaps the Philadelphia City Archives or another repository.

- Report of the Commission to Locate the Sites of the Frontier Forts of Pennsylvania. Harrisburg: Clarence M. Busch, 1896. 2 volumes. Excellent compendium of the frontier forts of most counties and people directly associated with them. Maps show the sites of each.

- George Washington Papers in the Manuscript Division of the Library of Congress.

- Crocker, Thomas E. Braddock’s March: How the Man Sent to Seize a Continent Changed American History. Yardley, PA: Westholme Publishing, LLC: 2009. Very readable account of Braddock’s defeat.

- Sipe, C. Hale, The Indian Wars of Pennsylvania. Lewisburg, PA: Wennawoods Publishing, 1999. This is the best published account, nearly day-by-day, of the clashes between white settlers and Indians during the French and Indian War and the subsequent Revolutionary War. About half of the book is concerned with each war. Archive.org.

- Stevens, Sylvester K. and Donald H. Kent, ed., Wilderness Chronicles of Northwestern Pennsylvania. Harrisburg: Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, 1941. WPA project, contains narrative descriptions and transcriptions of original documents, journals and letters.

Land:

- Proclamation of 1763 prevented most westward expansion

- Early settlers bought far western land from VA (before 1780)

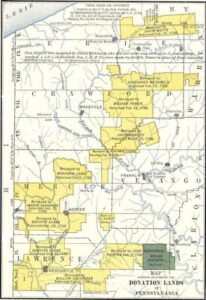

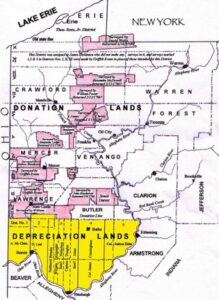

Donation Land and Depreciation Land Records: The PA Legislature used land to entice men to stay with their units until the war was over. If a member of the Pennsylvania Line served to the end of the war, he received Donation Land (often called bounty lands) in some western counties within Pennsylvania. Donation Land was given only to soldiers who served in Pennsylvania state units; Continental (federal) troops received land in Ohio and other locations, not in Pennsylvania.

Depreciation Land

Depreciation Land was designated as within the V formed by the Ohio and Allegheny rivers and was part of the New Purchase of 1784. Depreciation Certificates were given to Pennsylvania’s Revolutionary War veterans who had been paid in Continental Currency that had become worthless or “depreciated.” Men who had served in the federal militia (“Continental” forces) as part of the Pennsylvania Line or the Pennsylvania Navy were eligible for these Certificates of Depreciation that could be used to purchase land in the designated area, as were those who had been taken as prisoners of war.

The Depreciation Lands were divided into five districts, numbered from west to east, and assigned to district surveyors. If you click on the Depreciation Lands map above, you can see the faint district designations along the top of the opened map, as well as the districts superimposed on the counties. The Depreciation Land included what are now parts of Allegheny, Beaver, Butler, Lawrence and Armstrong Counties.

The surveyors were responsible for laying out tracts containing 200-350 acres each. Sales of the tract began in Philadelphia in the summer of 1785 after the surveys were completed. The money raised by sales of the tracts was to redeem the Depreciation Certificates that had been issued to soldiers. Few sales were made, however, because many people did not want to move to the wilderness and because Indians were still hostile to settlers. After the Battle of Fallen Timbers and the subsequent treaty in August 1794, it became safer territory. While some former soldiers did move to the land using their certificates, many of the veterans who received the certificates sold them to speculators or others who intended to settle on the land. For example, Francis White of Philadelphia, who created the first city directive in America, added the following advertisement in his 1785 directory of Philadelphia: “Francis White buys and sells continental money, depreciation certificates, final settlements, loan office-certificates, militia pay notes, officers and soldiers notes of every kind, and all other sorts of public securities, of this or any other state. He advances money and certificates to country people and others, for the land office, till their warrants are procured; and accommodates them with state money and with the exact sum in certificates they may want for the old or new purchase. He buys and sells on commission, houses, farms, lots,plantations, and back lands; and procures houses, rooms, boarding and lodging in the city, for strangers and others–All written orders to his office will be carefully and punctually attended to.”

The Depreciation Land Register shows the name of the surveyor, the district number, survey map number, a sequentially assigned tract number, name of the purchaser and size of the tract, patent date, patentee name, and the Survey Book and Patent Book and page number.

Soldiers who received Depreciation Interest Certificates (1782-1787) were published as “Soldiers Who Received Depreciation Pay as Per Cancelled Certificates on File in the Division of Public Records” in Pennsylvania Archives, Fifth Series, Volume IV, pp. 107-496 (use the “Browse” tab), which is freely available at Fold3. Search this source first, and then find an image of original certificates that have been digitized as “Depreciation Certificate Accounts (PA) 1781-1792.” Unsold tracts within the district were opened to all in 1792.

Donation Lands

Donation Lands: The same act (Purchase of 1784) that established the Depreciation Lands provided for Donation Lands to be set aside as a bonus for officers and soldiers who stayed in service until the end of the Revolutionary War. The Donation Land area was immediately north of the Depreciation Lands and west of the Allegheny River. The donation lands were distributed by rank in 10 surveying districts: colonels and generals received 500 acre tracts; regimental surgeons and mates, chaplains, majors and ensigns received 300-acre tracts; sergeants were given 250 acres; lieutenants, corporals, drummers, fifers, and privates were to receive 200-acre tracts. This land is now contained in Butler, Clarion, Crawford, Erie, Lawrence, Mercer, Venango and Warren Counties. The tracts were surveyed and numbered and drawn in a lottery system, one lottery for each of the four classes. See the Donation Land Register. The ledger will give the Survey Book and page number into which the survey was copied; download or print the copied survey posted by the Pennsylvania State Archives.

Virginia vs. Pennsylvania Claims:

Exasperated that the white man was constantly encroaching on their land, a war broke out over control of the continent in 1754 between the Indians, aided by French allies, and the British. This French and Indian War, during which both sides committed brutal atrocities, ended in 1763. After the war ended, King George III drew a line on the North American map and decreed that land west of the line was off-limits to settlers. He envisioned it as a “permanent” buffer zone between his subjects and Indians. This “Proclamation of 1763” forbidding settlement west of the Appalachian Mountains was heartily detested by his American subjects. A large number of people ignored the edict, propelled by the promise of vacant land. They walked, rode their horses, floated, and otherwise made their way over narrow paths into what is now Washington, Greene, Fayette, Westmoreland, Allegheny, and Beaver Counties.

- It was unclear which colony had the best claim to the land. Because Indians threatened to attack the surveyors if they continued west, the men surveying the Mason-Dixon Line stopped their work at the furthest western point separating Maryland from Pennsylvania in 1767. That left the entire western division between Pennsylvania and Virginia beyond Maryland undefined.

- Pennsylvania’s New Purchase grants (1769): Pennsylvania under the Penns had a long tradition of refusing to sell land until they obtained it from the Indians by treaty. Pennsylvania promulgated a major treaty at Fort Stanwix, New York, in 1768. On 23 Feb 1769, the Pennsylvania Land Office advertised that land was for sale in the “New Purchase.” Pennsylvania’s New Purchase land office closed after 1769, so most settlers who came to the frontier before 1776 became “squatters” or “pre-emptioners.” (see the “Indian Treaties” section above)

- Virginia’s “District of West Augusta”: After the New Purchase, Pennsylvania became distracted by yet another conflict: Connecticut claimed the northern 1/3 of Pennsylvania, sparking the Yankee-Pennamite Wars (see below). Probably marshaling its resources, the colony did not set up any courts in western Pennsylvania. However, in 1773 Lord Dunmore, the royal governor of Virginia, convened the House of Burgesses in Williamsburg to annex everything west of the Laurel Mountains to the Ohio River north to Fort Pitt, naming the area the District of West Augusta. Dunmore sent Dr. John Connelly (a Loyalist) to Fort Pitt to take possession of the fort (renaming it Fort Dunmore) and to make sure residents knew they were citizens of West Augusta, Virginia. Connelly also organized the militia in the area. Dunmore then moved the Augusta County court from Staunton, Virginia, to Fort Dunmore (later Fort Pitt, now Pittsburgh) in 1775 to administer the sparsely settled region. He aimed to cement Virginia’s claim to the vast territory. Pennsylvania was not entirely dormant in pressing its claims, however: both Virginia and Pennsylvania arrested, jailed, or fined officials from the other colony until the Mason-Dixon settled the boundary in Pennsylvania’s favor in 1780.

- Monongalia, Ohio, and Yohogaia Counties: In October 1776, the Virginia General Assembly subdivided the District of West Augusta into three smaller Virginia counties: Ohio, Yohogania, and Monongalia Counties. Men who lived in the area were sworn in as justices. Court days were held on a rotating basis: Ohio County met on the first Monday of the month, Monongalia on the second Monday, and Yohogania on the fourth Monday. (See Boyd Crumrine’s History of Washington County, Pennsylvania, pp. 183-185, for more detail).

- Revolutionary War: Every man between the ages of 16 and 53 was expected to enlist. Recruiters for both states were active in the area. Official and unofficial military units formed. While some of these companies marched east to join George Washington, most of them stayed in western Pennsylvania to protect their families along the dangerous frontier beyond the Appalachian Mountains. George Rogers Clark enlisted about 180 men from the area and they marched in the Illinois Campaign Indians, securing the Northwest Territory for America. For more comprehensive information regarding the Pennsylvania Militia, see the excellent article by Hannah Benner Roach, “The Pennsylvania Militia in 1777,” The Pennsylvania Genealogical Magazine 23 (No. 3, 1964), 161-230. Also see https://allthingsliberty.com/2014/06/explaining-pennsylvanias-militia/.

- Indians, riled up by the British and determined to do anything necessary to rid themselves of the encroaching white intruders, attacked frontier settlements. Likewise, American frontiersmen marched into Ohio to wipe out Indian villages. Western Pennsylvania became a second front in the Revolutionary War.

- While most of the men in the disputed area believed they were in Virginia and are listed in Virginia records, Congress also raised the Eighth Regiment of the Pennsylvania line which was composed mostly of men from Bedford and Westmoreland Counties. Frontiersmen are listed in both Virginia and Pennsylvania military records.

- Virginia claimants settled on the land, built cabins, and planted crops side-by-side with those who had purchased through the Pennsylvania lottery in 1769. However, it does not appear that any tracts were surveyed or patented by either colony before the Revolutionary War. Because of the turmoil of the Revolutionary War, the Pennsylvania land office in Philadelphia closed on December 2, 1776, “camped out” in Lancaster, and did not reopen for new warrants in western Pennsylvania until July 1, 1784. The land office in Westmoreland County, Pennsylvania, remained open but by that time most settlers believed they were living in Virginia. Virginia, of course, had established regional land offices by 1776 that were offering land for sale.

- 1780: The Mason-Dixon Line was finalized and the VA/PA claim was finally settled in favor of PA. On-the-ground surveys were not completed until 1784, so some disputes continued until that time.

After the Revolutionary War: Two Steps in the Process Transferring Jurisdiction from Virginia to Pennsylvania: When the boundary controversy was finally settled in May 1779 by the extension of the Mason-Dixon Line, Pennsylvania agreed to secure the land tracts to the family who had originally settled on the land, regardless of which colony issued the warrant. This required a 2-step process that apparently required two separate trips by the settlers: (1) obtain an official “Virginia Certificate” certifying the legitimate right to the claim; and (2) have the claim officially recognized by entering it into the “transfers” ledger registering the transfer to Pennsylvania jurisdiction.

- Step 1 (Virginia Certificates): To facilitate the transfer, Virginia’s General Assembly passed an act that allowed anyone who had settled on or before 24 Jun 1778 to pay for their tract if they had lived on it for a year or raised a crop of corn. Virginia also appointed commissioners to “to adjust the Titles to unpatented Lands in the Counties of Mononga Yohoga & Ohio.” The commissioners were to rotate sitting at six different sites in Monongalia, Ohio and Yohogania Counties, but the two offices specifically adjudicating the area within Pennsylvania met at Redstone Old Fort (also called Fort Burd, now Brownsville, Fayette County, PA) and Gabriel Cox’s Fort (near today’s Finleyville, Union Township, Washington County, PA). The Virginia commissioners had a laborious mission. The prospective landowner appeared before them and testified, presumably accompanied by the most credible witness they could find, that they had settled in a particular year or were requesting a right to settle. Unless there was a competing claimant or evidence to the contrary, the commissioners accepted the evidence and issued a “Virginia Certificate.” These Virginia commissioners painstakingly certified an individual’s right to a specific number of acres by writing their validation in longhand on pages of different sizes that are now bound into a volume titled Reports of Commissioners on Adjustment of Claims to Unpatented Lands[:] Monongalia, Yohogania, Ohio Counties[,] Virginia[,] West Virginia (original in the Monongalia County, WV, Courthouse.

- Step 2 (Transfers Ledger): By November 1779, Pennsylvania set up offices to accept the Virginia Certificates and officially record them. Thus was born the notebook or little ledger in the Pennsylvania State Archives that is the subject of this book. This “Transfers Ledger” became the foundational document transferring land formerly obtained under Virginia Certificates to Pennsylvania jurisdiction (officially named “Virginia Entries 1779-1780,” and it is housed in the Pennsylvania State Archives, Record Group 17, Series #17.209). Once again, it appears settlers had to make a weary trek, this time to a Pennsylvania land office, confirm who they were and that they had registered with the Virginia commissioners. Evidently the Pennsylvania Surveyor General’s office created a new table from the pages that now make up Reports of Commissioners on Adjustment of Claims to Unpatented Lands and distributed copies to the Pennsylvania commissioners so they could refer to them. As each settler came to attest to their claim, the Land Office must have verified his or her right through the “authenticated List transmitted from the Surv[eyo]r Gen[era]ls Office” (as written on 1785 survey in Survey Book A19, pg. 51, and many others.)

We have to remember the conditions that prevailed at the time: Indians continued to attack until 1783 and the thriving wildlife (panthers, bears, rattlesnakes, etc.) posed constant danger. Settlers did not make trips of such distance lightly, but the opportunity to own land caused them to put nearly every other consideration aside.

Eventually, tracts needed to be surveyed. Most surveys of Virginia claims transferred to Pennsylvania began to be conducted by Pennsylvania surveyors in 1784. It’s unclear whether the commissioners had issued Virginia Certificates directly to the settler in addition to the entry they made in Reports of Commissioners; if so, they seem to have disappeared. Some surveys contain verbatim transcriptions, starting with “We the commissioners….” It seems likely that at least some certificates were issued to the claimants since a few surveys state that a person “produced a Certificate from the Commissioners….”

Information in this “Transfers Ledger”

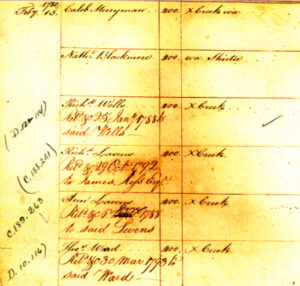

Example: Portion of page from the original 1779-1780 “Transfers Ledger.” The original notebook contained only four pieces of information: date of the entry into the ledger in the first column; name of the claimant in the second column (entered only after his/her claim was certified by the Virginia commissioners appointed to validate the landowner’s grant); number of acres claimed in the third column; and rough location in the fourth column (usually along a water course, like “X Creek” or Cross Creek). Note that survey references (Survey Book and page number) have been added in the first column in a different hand and ink in more recent times; and the “return of survey” in preparation for patenting the tract is written in a separate hand under the name of the claimant several years after the original 1780 entries.

The original “Transfers Ledger” was divided neatly into 4 columns with space between each person’s entry for later information: (1) the date of the transfer of the land to Pennsylvania authorities, not the date the land was settled; (2) name of the warrantee; (3) number of acres to which the claimant was entitled; and (4) general location (usually along a water course). In the original volume, about three-quarters of the tracts had some sort of identification for their locations in the right column.

For a complete transcription that corrects the transcription published in Pennsylvania Archives (3rd Series, Volume III, pp. 483-573 ) and adds the hundreds of annotations made in the margins of the notebook in the 120 years since the 1894 transcription was published see Sharon Cook MacInnes, Early Landowners of Pennsylvania: Land tracts Transferred from Virginia to Pennsylvania Jurisdiction 1779-1780 (Apollo, PA: Closson Press, 2020), Third Printing

- Other Resources:

- Core, Earl. The Monongahelia Story. Parsons, WV: McClain Printing Company, 2002. Volumes 1 and 2 contain information on early settlers of the border area between PA and today’s WV, land claims, and details of life on the frontier.

- MacInnes, Sharon Cook. Early Landowners of Pennsylvania: Atlas of Township Warrantee Maps of Fayette County, PA, 3rd edition.

- MacInnes, Sharon Cook. Early Landowners of Pennsylvania: Atlas of Township Warrantee Maps of Greene County, PA, 3rd edition.

- MacInnes, Sharon Cook. Early Landowners of Pennsylvania: Atlas of Township Warrantee Maps of Washington County, 3rd edition.

- MacInnes, Sharon Cook. Early Landowners of Pennsylvania: Atlas of Patent Maps of Westmoreland County

- Sims Index to Land Grants in West Virginia. Baltimore: Genealogical Publishing Co., Inc., 2003. Names of grantees, size of tract, and land book and page number for land grants “prior to the creation of the Virginia Land Office; by the Commonwealth of Virginia, of lands now embracing the State of West Virginia; and, by the State of West Virginia.” Of interest are the early land grants for Monongalia County and Ohio County.

- Veech, James. “List of Settlers in Fayette and in Contiguous Parts of Greene, Washington & Westmoreland Counties in 1772,” The Monongahela of Old. (Pittsburgh: No publisher, 1892), pp. 199-205. Download from Archive.org.

Connecticut vs. PA: Yankee-Pennamite War (1769-1771)

Charles II gave the same land to both colonies, and people from both colonies settled in the disputed territory. At the same time, the Iroquois claimed the Wyoming Valley of northern PA. Result: War! One of the final battles, taking place after the British lost at Saratoga and let their Indian allies loose, occurred at Forty Fort and is called the Wyoming Massacre. It left 150 widows and 600 orphans. Connecticut did not relinquish its claims until 1799.

- Connecticut’s “Susquehannah Settlers”: CT created “Westmoreland County” (not the same as Westmoreland County, PA); see http://explorepahistory.com/hmarker.php?markerId=1-A-17B and http://connecticuthistory.org/the-susquehanna-settlers/

Resources

- _____, “Connecticut’s Susquehanna Settlers” (Connecticut State Library); also see Connecticut Archives’ Susquehanna Settlers 1755-1796/ Western Lands 1783-1789 and Susquehannah Settlers Second Series, 1771-1797/ Western Lands Second Series 1783-1819

- _____, “The Right of the Governor and Company, of the Colony of Connecticut, To claim and Hold the Lands Within the Limits of Their Charter, Lying West of the Province of New York” (Hartford, CT, Eban. Watson, 1773)

- Julian P. Boyd, editor, The Susquehannah Company Papers, (Wilkes-Barre: Wyoming Historical & Geological Society, 1930-1933), Volumes 1-4

- William Henry Egle, Pennsylvania Archives, 2nd series, Vol. 18 (use the “Browse” tab)

- Henry M. Hoyt, “Brief of a Title in the Seventeen Townships in the County of Luzerne: A Syllabus of the Controversy Between Connecticut and Pennsylvania” (Harrisburg: Lane S. Hart, 1879):

- Donna Bingham Munger, “Six Steps to Susquehanna Company Settlers,” Pennsylvania Genealogical Magazine 37 (1991): 125-34.

- Donna Bingham Munger, Connecticut’s Pennsylvania “Colony”: Susquehanna Company Proprietors, Settlers and Claimants. Westminster, MD: Heritage Books, 2007 ($). Volume 1 contains an overview and information about the Susquehanna Company shareholders, plus the deeds from the company to purchasers. 2 contains all names found on several lists of inhabitants, including the 1,150 names on the 1801 petition to Congress asking for relief, and tax lists for 1776-1780. Vol. 3 contains the settlers who claimed and received title to their tracts from Pennsylvania, including chain of title.

- Fletcher Weyburn, Following the Connecticut trail from Delaware River to Susquehanna Valley (Scranton: The Anthracite Press, Inc., 1932)

- A free index to the surveys and patents in Luzerne County (now Bradford, Lackawanna, Luzerne and Wyoming Counties) originally claimed by settlers from Connecticut.

- Luzerne County Historical Society has early township proprietors’ records, land records, tax lists and church records.

Maryland vs. Pennsylvania Claims:

Pennsylvania’s Charter of 1681 set the boundary “on the south by a circle drawne at 12 miles distance from New Castle Northward and Westward unto the beginning of the 40th degree of Northern Latitude….” but New Castle lay 25 miles south of the 40th Philadelphia was south of 40th parallel. Both MD and PA sold land in each other’s territory. Some records are double-entered in MD and PA.

- 1729: Lord Baltimore claims parts of York & Adams Counties so the Penns send 140 fighting Scots-Irish families from Ulster to settle Cumberland Valley and hold it for PA; more follow. Germans also funnel to York/Adams/Franklin Counties before 1736 treaty.

- 1727-30: Lord Baltimore grants 10,000 acres “Digges Choice” to John Digges. Boundary later settled in PA’s favor.

- Hively, Neal Otto. The Manor of Springettsbury, York County, PA: Its History and Early Settlers. Privately printed, 1997. Also separate accompanying map 20.

- Weaner, Arthur. Index to the Map of Digge’s Choice. Gettysburg: Adams County Historical Society, 2005. $5 from the society (also see http://www.cynthiaswope.com/withinthevines/manordiggeschoice.html)

- 1730: Marylander Thomas Cresap opens ferry service across Susquehanna River and began acting as a Maryland land agent; PA Germans purchased farms from him. Records may be in MD. Finally resolved by Mason-Dixon Line in 1767 (http://www.cynthiaswope.com/withinthevines/penna/adamscounty.html and http://www.cynthiaswope.com/withinthevines/manorspringcressapswar.html)

- 1734: Blunston Licenses (earliest settlers in Cumberland Valley, York, Adams): Because the Penns allow settlement before receiving the land through a treaty, they issue special Blunston Licenses. For a further explanation, see “Blunston Licenses and their Background” on Ancestry

- Transcriptions of licenses: Pennsylvania Genealogical Magazine, March 1931 (volume 11, No. 2, pp. 180-185); PGM Volume 11, No. 3, 269-275; and PGM volume 12, No. 1, pp. 62-70)

- 1767: Mason-Dixon Line separating MD from PA is completed

A little background is in order: The original three counties–Philadelphia, Chester, and Bucks–were established in 1682; other counties were set up as people became dense enough to warrant a courthouse.

- The first Warrant Registers (“Original Purchase Registers” and “Old Rights Warrant Register”) began documenting sales of unknown Pennsylvania land before William Penn even left England when the topography wasn’t known. Therefore many people purchased rights to hundreds or thousands of acres sight unseen. Some new owners of land never left England but sold their rights. Others tried to claim the same or overlapping land. The original ledgers were scrapped in favor of new registers in 1733.

- As each county came into existence, the PA Land Office created a new register and began entering the land sales as they occurred. The last county to be formed, Lackawanna, finally came into existence in 1878. Thus, the warrantees are entered under the county as it existed at the time of the sale, then under the letter beginning the last name, and then chronologically thereafter.

- For the researcher, having all of the county Warrant Registers in one place makes the search of the records far easier.

For example, if your Snyder County ancestor settled earlier than 1855 when it was carved from Union County, you will have to check Union County’s Warrant Register. However, Union County was created from Northumberland County in 1813. If your ancestor bought his land there before 1813, his transaction will be recorded in the Northumberland County Warrant Register. Northumberland was created in 1772 from several counties: the area that later became Snyder County was formerly in Berks and Cumberland Counties. In other words, you may have to access multiple Warrant Registers to find your ancestor’s information.

Knowing the county as it existed when your ancestor lived there rather than the county as it is today is essential—wills, court records, and deeds were filed in the existing courthouse and normally were not transferred to the new county. From the original three counties (Bucks, Chester and Philadelphia), PA has grown to 67 so you must know the parent counties!

- Sharon Cook MacInnes, The Keystone: Essential Guide to Pennsylvania Historical County Records (Silver Spring, MD: Ancestor Tracks, 2022). One chapter for each of the 67 counties that outlines county boundary changes based on the Newberry Atlas of Historical Boundaries; synopsis of where records are files for each time period; links to free 19th-century county landowner maps and atlases; links to free online published county histories; links to online county Grantor/Grantee Indexes and Deed Books; links to state land records that precede county Deed Books (connected early tract maps, Warrant Registers, Patent Registers, etc.); summary chart of the formation of each township within the county, including townships that no longer exist

- Automated changing county lines for PA (scroll down and click on a year of interest to see Pennsylvania’s counties as of that year).

- To see how the counties were formed: Genealogical Map of the Counties (right-click to open in new tab, enlarge it, and save on your computer)

- To see Pennsylvania in each census year superimposed over a current map of the counties, use William Dollarhide’s Map Guide to the U.S. Federal Censuses (log on to HeritageQuest (through your library, click on “Maps,” then your state of choice. Census years (to 1920) are on the left. Some county maps by Dollarhide are also in Red Book: American State, County, and Town Sources edited by Alice Eichholz.

- Download the KMZ file for Pennsylvania (which works with Google Earth), as well as the PDF booklet on Pennsylvania boundaries, from Newberry Atlas of Historical County Boundaries

- Pennsylvania Online Gazetteer (current)

- Linkpendium

- For current township maps and some historic map links: USGenWeb Digital Map Library for Pennsylvania

- Search for current or obsolete names (abandoned cemetery, church, crossing, forest, populated place, post office, etc.: GNIS (Geographic Names Information System)

You can order black-and-white copies of the original warrant, survey, and patent from the Pennsylvania State Archives by using their order form.

- There is no search fee if you use the information provided in our atlas for date and Patent Book and page number; date and Survey Book and page number; and type of warrant (Survey or Accept), warrantee name and date of warrant.

- If you do not know the specific document number or page number, there is a $25 search fee per name or tract per county if you are not a resident of Pennsylvania, or $15 if you are a Pennsylvania resident

- The fee for uncertified copies is $3.00 for copies (including front and reverse) of each warrant, survey, or patent. Copies will not be made until the fee(s) are received.

- Be sure to specify that you want a copy of the original survey or they will provide a copy of the online “copied” survey.

While Pennsylvania was founded by Quakers who generally did not abide by owning human beings, William Penn kept at least three enslaved people. Pennsylvania was also heavily Germanic, and Germans tended to view slavery as an abomination. However, not all Germans held this view and some Germans kept enslaved people. While slavery in Pennsylvania was not the norm, it was not abolished until 1847.

While Pennsylvania was founded by Quakers who generally did not abide by owning human beings, William Penn kept at least three enslaved people. Pennsylvania was also heavily Germanic, and Germans tended to view slavery as an abomination. However, not all Germans held this view and some Germans kept enslaved people. While slavery in Pennsylvania was not the norm, it was not abolished until 1847.

- Slavery decreased over the years, but a great deal of prejudice remained throughout the years. Enslaved people were required to be registered annually until 1847 but were usually listed by how many their enslaver owned rather than by name.

- 1 Mar 1780: The “Gradual Abolition Act” was passed and stated that children of enslaved people born after that date would be treated as indentured servants required to serve their mother’s masters as servants until the age of 28 (the concept was that the master would care for these children until they reached 14, but would be paid back with 14 years of labor). Enslaved people born before the 1780 act remained enslaved for life unless manumitted.

- The 1780 law also forbade the importation of slaves into the state. Enslavers had to register their slaves by 1 November 1780. Punishment for not registering would be the immediate manumission of the “servant” in question.

- [Note, however, that the “Negro Register” of Washington County (which included a portion of West Virginia) was kept from 1782 until 1851, although most entries ended in 1820. Enslavers declared that elderly slaves were kept so they could be cared for rather than left to fend for themselves.]

- 1788: More stringent laws were passed in 1788 banned separating immediate family members.

- 1847: Slavery was abolished in 1847, and all remaining enslaved people (about 60-100 state-wide, almost all elderly) were freed. The following examples of records of the enslaved are:

- Cumberland Co. Clerk of Courts “Slave & Slave Owners Register 1780 (Nov) – 1841″

- Slave Matters, Miscellaneous from Clerk of Courts

- Early enslaved censuses for Bedford, Bucks, Cumberland, Dauphin, Lancaster Counties are in the Pennsylvania State Archives in Harrisburg.

- Chester Co. maintains images on a database for in-person visits within the Chester County Archives in West Chester and will also look up and send copies.

- Some registries are filed with the county Prothonotary or have been transferred to the Pennsylvania State Archives (for example, the Bucks Co. “Office of the Prothonotary, Register of Slaves, 1783-1830″ is online).

- Names of enslaved people are sometimes included on Septennial Census Returns (composed of tax lists). My research in the 1800 Septennial Census shows lists of enslaved at the end or within a page of each county’s enumeration; some, however, are just a count in each township.

- 1837/1838 and 1856: The Pennsylvania Abolition Society conducted a census of all blacks in Philadelphia and its suburbs.

- 1847: Quakers took a census of African-Americans (free) living in Philadelphia.

- “Slavery and Underground Railroad Resources” has links to images of registers of African-Americans and enslaved in Adams, Bedford, Bucks, Centre, Cumberland, Fayette, Lancaster, and Washington Counties.

- The Underground Railroad in Lancaster Co. gives a timeline and mentions Robert Smedley’s The Underground Railroad in Chester and Neighboring Counties of Pennsylvania which is online

- Under project manager and editor Eric Grundset, the DAR (Daughters of the American Revolution) produced Forgotten Patriots: African American and American Indian Patriots in the Revolutionary War (Washington, D.C.: NSDAR, 2008). This is “A Guide to Service, Sources and Studies” rather than a list of soldiers although some are mentioned by name. Chapter 8 gives Pennsylvania resources. In 2012, DAR published a supplement.

- Ruth E. Hodge, Guide to African American Resources at the Pennsylvania State Archives. Harrisburg: Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission, 2000. Hodge is an associate archivist at the archives and discusses record groups, microfilm, manuscripts, and photos. Much of the content of this book is online.

- Robert B. Shaw, “Pennsylvania” in Legal History of Slavery in the United States (Potsdam, NY: Northern Press, 1991).

- FamilySearch has a portal for their Freedmen’s Bureau Project. Also see their wiki entry “African American Resources for Pennsylvania.“

- The University of Pittsburgh has an excellent project “Free at Last?”: Slavery in Pittsburgh in the 18th and 19th Centuries“

- While this “African American Online Genealogical Records” page on FamilySearch does not deal specifically with Pennsylvania, it has many links to topics of interest such as Southern Claims Commission, Freedman’s Bureau Records, African American newspapers, Blacks who served in the Civil War, etc.